YARA Rules: Strings. Conditions. Caught.

- Aastha Thakker

- 2 days ago

- 6 min read

If you’re in cybersecurity, you’ve almost certainly dealt with malware or at the very least, heard the news about it. But here’s a question: how do you find it when it’s already hiding on a system, hiding in like a perfectly normal file?

The answer, in many SOC environments and threat intel teams, is YARA. If you’ve heard of it, great, you’re already know the game. If you haven’t? Well, you just heard it right now. Either way, get hands on.

You must understand what a YARA rule is, how to write it and how to use it to detect a real piece of malware behavior on a system. This is full hands-on.

What Is YARA and Why Should You Care?

YARA is a signature or pattern matching tool designed specifically for identifying and classifying malware.

Created by Victor Alvarez at VirusTotal, YARA lets you write rules in a human-readable format that describe characteristics of malware families. These characteristics can be strings, byte patterns, regular expressions, or even logical conditions combining all of the above.

YARA stands for “Yet Another Ridiculous Acronym”, yes, really. But don’t let the name fool you. It’s one of the most useful tools in a threat hunting or malware analysis.

Why Does YARA Matter?

Antivirus signatures are great until they aren’t. Malware authors mutate their code constantly to evade detection. YARA gives you the power to write flexible rules that catch not just one variant of malware, but entire families because you’re targeting behavior and structure, not just a single hash.

YARA is used by:

SOC analysts for triage and alert enrichment

Malware researchers to classify samples

Threat hunters to proactively find evil on endpoints

Incident responders to scan compromised systems

Platforms like VirusTotal, Malwarebytes, and CAPE Sandbox

Installing YARA: Get the Tool Ready

Installation

Before we write any rules, let’s get YARA installed. It supports Linux, macOS, and Windows.

Linux (Ubuntu/Debian):

sudo apt-get install yaramacOS (Homebrew):

brew install yaraWindows:

Download the precompiled binaries from the official YARA GitHub releases page: https://github.com/VirusTotal/yara/releases

Verify Installation:

yara --versionIf you see a version number, you’re good to go. If not, double-check your PATH variable.

For Python lovers: you can also install the Python bindings with pip install yara-python and write rules programmatically. We’ll touch on this later.

Anatomy of a YARA Rule

Every YARA rule follows a specific structure. Before I throw code at you, understand what each part means. This is the skeleton of a YARA rule:

rule RuleName {

meta:

author = "Name: Aastha Thakker"

description = "What this rule detects"

date = "2026-02-19"

strings:

$string1 = "suspicious_text"

$string2 = { 4D 5A 90 00 } // hex bytes

$regex1 = /bad[_-]pattern/i // regex

condition:

any of them

}Breaking Down Each Section

Rule Header: The rule starts with the keyword rule followed by a unique name. Use snake_case or PascalCase, just keep it consistent and descriptive. Names like detect_mimikatz_strings are infinitely better than rule1.

Meta Section: This is optional but important for real-world use. This section doesn’t affect detection, but it tells your teammates (and future-you) what the rule does, who wrote it, and when.

Strings Section: This is where the work happens. You define the patterns you want to look for:

Text strings: Plain text patterns, case-sensitive by default.

Hex patterns: Raw byte sequences, great for shellcode or binary signatures.

Regular expressions: Flexible pattern matching using regex syntax.

Condition Section: This is the brain of your rule. It defines WHEN the rule fires. Conditions can be simple or complex:

condition: $string1 // fires if string1 is found

condition: all of them // fires if ALL strings are found

condition: any of ($string1, $string2) // fires if any of these match

condition: $string1 and filesize < 500KB // combo condition

condition: #string1 > 3 // string1 appears more than 3 timesWriting Your First YARA Rule

Theory is great. Practice is better. Let’s write a real rule — step by step.

Scenario: Detecting a malware sample with Strings

Download a sample malware file from MalwareBazaar inside a virtual machine.

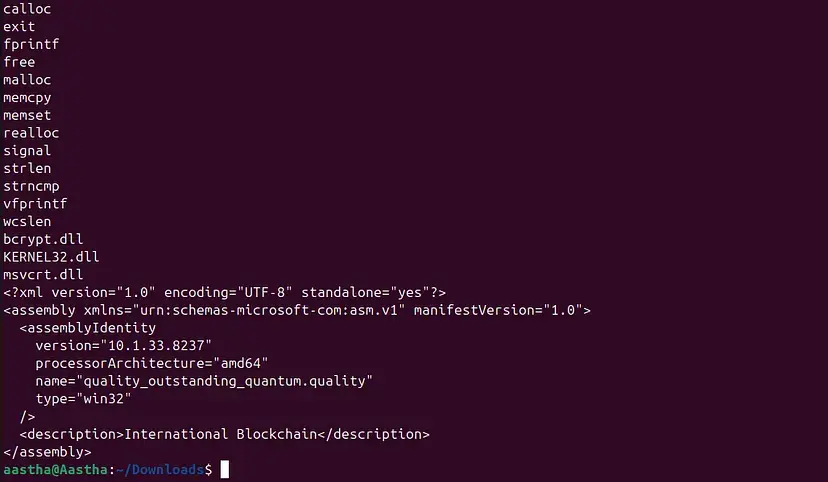

Now type ‘strings sample-malware1.exe’ to get the strings from the malware. You will get an ouput somewhat like this:

Now from the sigtool, get the hex value of any copied string. Copy a smaller and identifiable string for better understanding. For this you will require clamav to be installed. If you have not already installed then use this command “sudo apt install clamav”. Once you get this hex dump, copy it for further use.

echo “string-you-copied” | sigtool --hex-dump

Note: the last 0a you can see in the string denotes space at the end. If any error comes up, try removing that.

Create a file with ‘nano yara-testrule1.yar’. Add the following rule and save the file.

rule Detect_Sample_malware1

{

meta:

author = "Aastha"

description = "Detects sample-malware1.exe"

severity = "testing-low"

strings:

$s1 = { 6e 61 6d 65 3d 71 75 61 6c 69 74 79 5f 6f 75 74 73 74 61 6e 64 69 6e 67 5f }

$s2 = "malware" nocase

$s3 = "International Blockchain"

$s4 = ".onion" nocase

condition:

1 of ($s*)

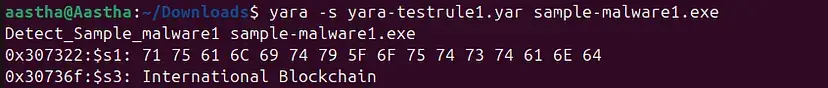

}5. Now, run this command to verify the rule. ‘-s’ is to check which condition was triggered.

yara -s yara-testrule1.yar sample-malware1.exe

You can scan the entire folder also with one rule file. It will check the condition in the whole directory.

You can find the hash of the file from this command.

sha256sum filename.exe

Now for checking the hash value, you need to import hash function. You can either modify the older file or create a new one with this syntax. This rule calculates the SHA256 hash of the entire file and compare it with the given hash. If both match, the rule triggers.

import "hash"

rule Detect_hash

{

meta:

author = "Aastha"

sha256 = "sample-malware1.exe"

condition:

hash.sha256(0, filesize) == "ec7977cc97003f2a34b13edebfc7db888fc22c4dde96b7bccca1ddbd2e191ac1"

}

-s: Displays which strings matched, and their offset inside the file.

0x30736f — offset (location in file)

$s3 — string identifier from ruleInternational Blockchain — matched string

-D: Print module data (Debug module info), Shows internal module data, like hash values, PE metadata, imported functions, file properties.

8. PE analysis using yara. Create a file ‘pe.yar’ and paste this.

import "pe"

rule Suspicious_PE {

meta:

description = "PE file with suspicious import and small section count"

condition:

pe.is_pe and

pe.imports("kernel32.dll", "VirtualAlloc") and

pe.imports("kernel32.dll", "CreateRemoteThread") and

pe.number_of_sections < 4

}

VirtualAlloc + CreateRemoteThread is a classic shellcode injection combo. A PE with both of these AND fewer than 4 sections is worth investigating. VirtualAlloc allocates memory inside a process, and CreateRemoteThread executes code inside another process. This combination is commonly used in process injection attacks.

9. Want to scan your entire system? Use recursive scanning.

yara -r -s yara-testrule1.yar /home/

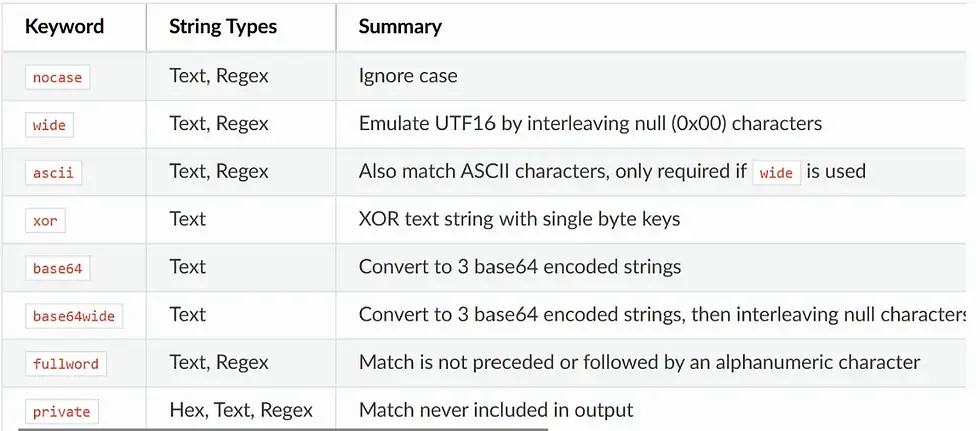

YARA string modifiers give you fine-grained control. This is the basic and most used string modifiers you can refer.

YARA Feeds and Community Rules

You don’t have to write every rule from scratch. The security community is incredibly generous:

YARA-Rules on GitHub: https://github.com/Yara-Rules/rules massive community repo

VirusTotal: Supports YARA hunting across their entire malware corpus

Malpedia: Curated YARA rules linked to malware families

InQuest Labs: High-quality threat intelligence with YARA signatures

Start with community rules, test them against known-good files, tune for false positives, then adapt them for your environment. Never blindly deploy rules from the internet without validation.

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Writing Overly Broad Rules → High False Positives: A rule that matches on strings like “password” or “error” will fire on thousands of legitimate files. Always test your rules against a baseline of known-good files before deployment.

Ignoring Performance: YARA rules run against every file you point them at. Complex regex patterns or rules with hundreds of strings can be slow. Profile your rulesets and optimize for performance in production environments.

Not Using Modules: Beginners often stick to basic string matching when modules like pe, elf, or hash can give them far more precision with fewer false positives.

Not Versioning Rules: Treat your YARA rules like code. Use Git. Tag versions. Document changes in the meta section with dates and revision notes. Six months from now, you’ll thank yourself.

YARA is one of those tools that separates reactive defenders from proactive hunters. You don’t wait for an alert, you go looking for threats yourself, on your terms, with your rules.

The best part? You’ve already started. You have a working rule. Now go find something malicious and then write a rule that catches it.

Comments